Wayne Visser, Ph.D.

By Cassandra West

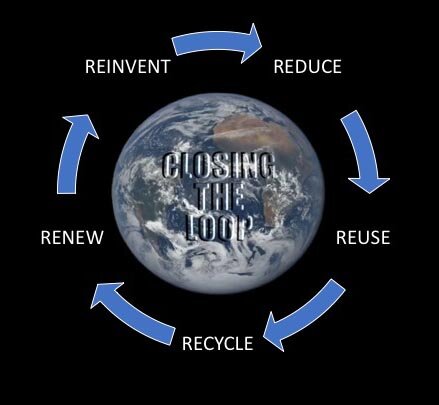

A global sustainability expert, Wayne Visser, Ph.D., is a fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Sustainability Leadership and holds the chair in Sustainable Transformation Antwerp Management School in Belgium. He is the co-presenter of the documentary, “Closing the Loop,” which explores five key strategies for achieving circularity—reduce, reuse, recycle, renew and reinvent—by showcasing examples from Europe, Latin America and Africa. The documentary features insights from experts from the World Economic Forum and the Universities of Cambridge and Harvard. One Earth Film Festival publicist Cassandra West interviewed Visser via a Zoom chat recently.

“Closing the Loop” will be screened Wednesday, April 21, 6:30 to 9 p.m. Central Daylight Time during the Earth Week Mini Film Festival.

Q: What does “closing the loop” mean?

A: Closing the loop means is a documentary film, the first feature length documentary film in the world on the circular economy. The circular economy is the way that we redesign how we make things and how we dispose of things, so that ultimately both materials and resources keep getting recycled either back to nature or in manufacturing.

Q: Where do you think we're headed if we don't close the loop?

A: Well, in the opening line of the documentary, I say “unless we go to circular, it's game over for the planet, game over for society.” So it doesn't get stronger than that. I really believe that there's no way we can continue to grow, which is what every country, every business, every politician strives to do with a linear economy because we're living on a finite planet. And it simply doesn't add up. So the only way we avoid catastrophe (by which I mean the complete ecological breakdown leading to societal collapse) is by adopting the circular economy.

Q: Could you go into a little bit more detail of how that looks? How would a city or country create a circular economy?

A: Essentially, what it means is every product has to be designed either to be able to go back harmlessly to nature, so created from natural materials and able to biodegrade or to compost back in nature without any harmful side effects. Or it has to be designed to be recaptured at the end of its life and to be turned back into materials to be made back into products. And powering that whole system has to be 100% renewable energy, so solar, wind and so on. That's the only way that we do it.

There are already companies that are able to take that mixed plastic and turn it back into products, so it's just a case of designing for easy disassembly so that whether it's a car or a mobile phone, it can be easily taken apart. So we can know what's in it and how what's in it needs to be treated or recycled, and that's not something that most manufacturers have been very good at, because they haven't been pressured to do that.

Q: You traveled to many countries to make this film.

A: Yes. Rather than just go to rich countries that had a lot of high technology, sophisticated technology, we also went to South America, specifically to Ecuador, and we went to South Africa. What we tried to show there is how the circular economy is actually creating jobs. It's creating livelihoods for people, and so you've got a double benefit. You've got a social and economic benefit as well as the environmental. And some of those stories that we show in the documentary are very powerful because they are human stories. When you talk about traveling, we traveled in Europe as well to Italy, to the Netherlands, Germany and the UK. They all had their own positive stories. That was the point of the documentary: to show solutions. But the ones that really moved me and probably move the audience are the ones where you can really see this is changing people’s lives.

Q: One Earth Film Festival is really about bringing forth films that offer solutions, so that makes your film well-chosen for the festival. Can you talk about challenges you encountered in making the film?

A: As with all films, funding is the first, biggest challenge. We managed to get some of the cases we featured to contribute to the costs. But that meant that in the end, we didn't film anywhere in Asia because there simply wasn't funding from the cases that we found. [There] was no shortage of great examples from Asia but just no funding forthcoming. So that was one of the barriers right up front. We were on a small budget that limited where we could go and how much we could do. In terms of the filmmaking itself, it took longer than if we had a nice big budget.

Q: How long did it take to make the documentary?

A: About two years from start to finish, but there were parts of it we could've sped up if somebody had been working on it full time. Although we say we like to find solutions, the media loves dramatic, catastrophic documentaries. We’ve got “Seaspiracy” at the moment on Netflix. It's pretty depressing stuff. It's worth watching [because] it exposes a lot of the damage of the fishing industry. But there's like two minutes at the end of solutions in a 90-minute documentary. And it gets all the attention because it's so controversial. So I think that's been one of the barriers with [“Closing the Loop”]. We never got it onto Netflix or anything like that. In the end, we just open sourced it, and we put it on YouTube to let as many people watch it as possible, but probably it's better if it gets onto those big channels, [and] that could still happen.

Q: And, finally, are you optimistic?

A: Yeah, in fact, I've written a poem called “Be an Optimist,” and it starts, “be an optimist not because the future is bright but because bright people are working to make the future better.” And that spirit is my spirit of optimism, which is to say that the challenges are there. They’re big, they’re urgent, but there is so much momentum behind the solutions, behind the collaboration, that's what gives me optimism. It's showing that it is possible to redesign this. I'm fortunate that I lived through the South African transition from apartheid to democracy, and for a whole generation it was not possible to defeat that racist regime until it was. Then it went very quickly. I always keep that in mind, that in complex living systems, change can happen very quickly, and it can be changed for the better — or for the worse. But [the circular] economy is something that we could see adopted much more quickly than many people expect if we get the momentum going.

Some of the transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.