“Changing” by Alisa Singer, a Chicago area artist. Source: IPCC. Artwork was commissioned for the cover of the AR6 WG1 Report. Click the image to visit Singer’s website, Environmental Graphiti. Most of the following images will also lead to Singer’s Art>Science connections.

Source: IPCC AR6 Figure SPM.5

By David Holmquist

On August 9, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (UNIPCC, or simply, IPCC) released the first installment of its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). The nearly 4,000-word document compiled by Working Group 1 addresses the most recent understanding of the Physical Science Basis of global climate change. The group was composed of 234 authors from around the world who evaluated more than 14,000 peer-reviewed studies.

A second installment, focused on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, will be released in February 2022. The third Working Group Report, to be released in March 2022, will address Mitigation of Climate Change. Finally, the conclusions and recommendations of all three Working Group Reports will be brought together in the AR6 Synthesis Report, scheduled for release in September 2022.

The last Synthesis Report (AR5) was published in 2014. Prior reports were published at roughly six-year intervals, going back to the First Assessment Report in 1990. Over the three decades since, scientists’ understanding of Earth’s physical systems has expanded at a truly extraordinary pace, and with it the specificity and confidence of their analyses and projections. As an analysis in The Washington Post pointed out, the phrase “virtually certain” appears nearly a dozen times in the AR6 Summary for Policymakers (SPM); in the SPM for AR5, there are no instances of that phrase. The phrase “high confidence” appears over 100 times compared to 50 times in the AR5 SPM.

Among the reasons for this rapid narrowing of expert consensus on the physical science basis:

Increased numbers of scientists and institutions engaged in climate research

Increased opportunities for connection among these researchers through internet, publishing and conference platforms (including the IPCC’s Assessment Report framework)

Vastly increased computational power, which has allowed for exponential growth in the development of climate models and their validation against observed changes

Vastly increased observational data, in terms of volume, quality and time scale, which contributes to the refinement of those climate models

Considerable progress in the collection and analysis of paleoclimate data (from ice cores and other geologic formations)

One example of this explosion in observational data is the deployment of Argo and Deep Argo “floats” in all the world’s oceans. First proposed in 1999, Argo has grown to a networked array of 4,000 sensing buoys that can descend to depths up to 6,000 meters and deliver data to a satellite network referred to as Jason (I’ll leave it to the reader to parse the classical reference) as they surface. The integrated network is an international project which collects data on ocean temperature, salinity and acidity. The network also monitors global ocean currents. These floats are arrayed on a grid determined and refined by the satellite data they collect. As a result, scientists understand the ocean ecosystem much, much, much better than they did just twenty years ago, when the Third Assessment Report was published. And they are not reassured.

The implications of these data—and many others from the report—are, in the words of United Nations Secretary General António Guterres, “a code red for humanity.”

Known Unknowns

A crucial, and unpredictable, factor in our climate future is the occurrence of ‘tipping points.’ If you followed the link above regarding ocean currents, you’ll have noticed the statement “… if humans are not able to limit warming, the system could eventually reach a tipping point, throwing global climate patterns into disarray.”

The AR6 WG1 report makes it clear that there are grave uncertainties regarding possible abrupt climate feedbacks, and that earlier projections of gradual and linear changes to earth systems in response to increasing greenhouse gas emissions can no longer be relied upon when considering possible climate futures. The report states:

The probability of low-likelihood, high impact outcomes increases with higher global warming levels (high confidence). Abrupt responses and tipping points of the climate system, such as strongly increased Antarctic ice sheet melt and forest dieback, cannot be ruled out (high confidence).

Some of the possible “abrupt responses” are the collapse of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, the shutdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which drives the Gulf Stream, vast methane releases from arctic tundra and methane hydrates on the Arctic Ocean shelf of Russia, the disappearance of summer arctic sea ice. None of these events are fully included in climate models because their probabilities cannot be established beyond speculation.

The Carbon Budget

The report updates the “carbon budget”—the measure of how much carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gasses we can emit in order to stay within the 1.5-2.0 degree C goal of the Paris Climate Agreement. There is some modest good news in these estimates, which are quite close to those released by the IPCC in a special report in 2018. Due to improvements in methodology, the remaining carbon budget “headroom” is substantially larger than was projected in AR5. That said, the challenge is still daunting.

Source: IPCC AR6 Table SPM.1

Sources and Sinks

In line with other recent studies, the report asserts with high confidence that land and ocean carbon sinks are nearing their capacity to absorb continued high levels of emissions—an imbalance of sources and sinks. Therefore, the atmosphere will bear the burden of continuing emissions, and the greenhouse effect will become more pronounced. This imbalance is illustrated by the following graph, and by Alisa Singer’s art.

Source: IPCC AR6 Figure SPM.5

Man or Nature?

The very first finding in the report is this:

It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.

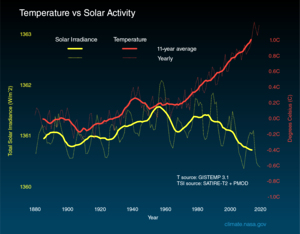

I strongly suspect that this is the first time the word “unequivocal” has appeared in an IPCC report, given the IPPC’s “calibrated language” and the fact that these reports require both scientific and political consensus. Alisa Singer illustrated one thread of the evidence for human-caused climate change in this piece:

The IPCC report also rules out other forms of natural variation as explanations for the extraordinary warming since the dawn of the industrial revolution, including orbital variations and variations in volcanic activity.

The Man or Nature debate is over. But neither is the winner.

Watch for a commentary of the Working Group 2 report when it is released in February 2022.